The New Exoticism?

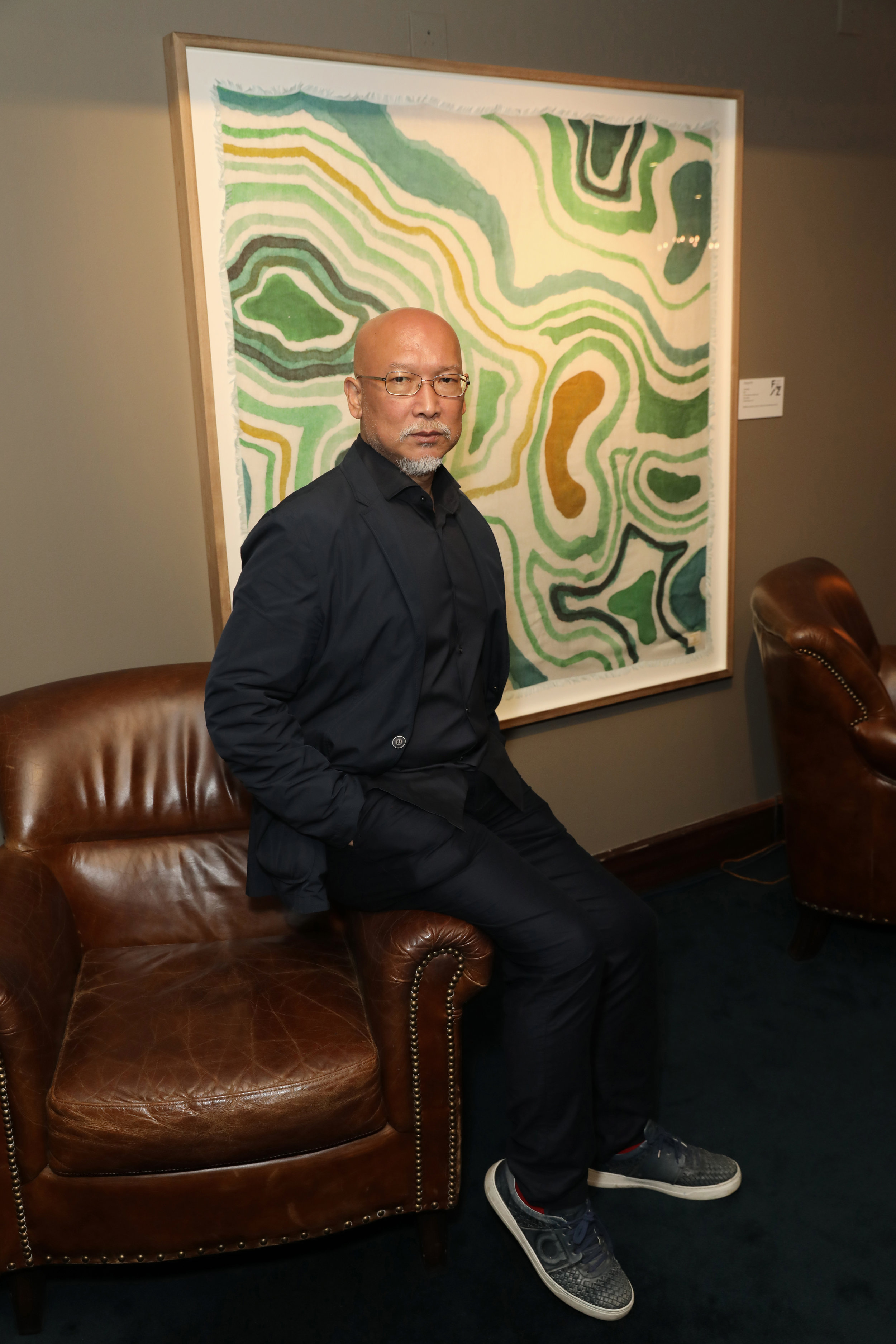

Fortnum's X Zhang Enli. Photograph by Peter Mallet.

Bernadine Bröcker Wieder is CEO and Co-Founder of Vastari Group, an online platform securely connecting private collectors of art, exhibition producers, venues and museums. She is a young ambassador to the Museum of London, an advisor to We Are Museums, Cromwell Place, Artnome, the Christie's Employers Advisory Group and a mentor at the Founder Institute. In 2018 she was selected for Apollo Magazine's 40 under 40 Europe, and Bernadine and co-founder Francesca Polo were shortlisted for the Natwest Entrepreneur of the Year Award in 2017. Bernadine holds a Master’s degree in History of Art and Art-World Practice from Christie’s Education/The University of Glasgow and a Bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts from Parsons School of Design, New York.

The New Exoticism?

An exhibition of Zhang Enli opens at F&M for the latest collaboration between a luxury brand and a contemporary artist

Exoticism — what a word. It is often associated with 19th-century Orientalism and a slightly inept but aesthetically pleasing appropriation of otherness.

There is a perfect example of this type of Orientalism with a capital “O” at Fortnum & Mason right now — and I am not talking about the works by Zhang Enli hanging throughout the queen's official grocery store until the 18th of October. It is, instead, a piece that you can spot on the first floor heading towards the cloakroom in the corner. Hanging on the wall, minding its own business, is an image of some kind of harem scene from 1935 by an unnamed, anonymous artist, that was presumably used as inspiration for a print or product at some point.

This image, where the artist has become anonymous, in a similar way to the artisans who help build the luxury products sold all throughout Fortnum's floors. This is how exoticism works — it takes away a great proportion of the identity of the maker. It values ephemerality, recalling an imagined reality of otherness that is idealised and inspiring, and, in general, is also greatly looked down upon by the 'real' art world.

How does this relate to the Zhang Enli commission at hand? Well, a similar thing has happened with the works commissioned by Fortnum’s from this eminent artist for this collaboration, but in the reverse.

It is a risky move to commission a Chinese artist to create a series of works for such a British brand. Will it become tacky, like an ill-considered tattoo of a Chinese character on a shoulder blade, or a rushed piece of 18th-century export porcelain with caricatures of white people [2] - or could it manage to respect each represented party?

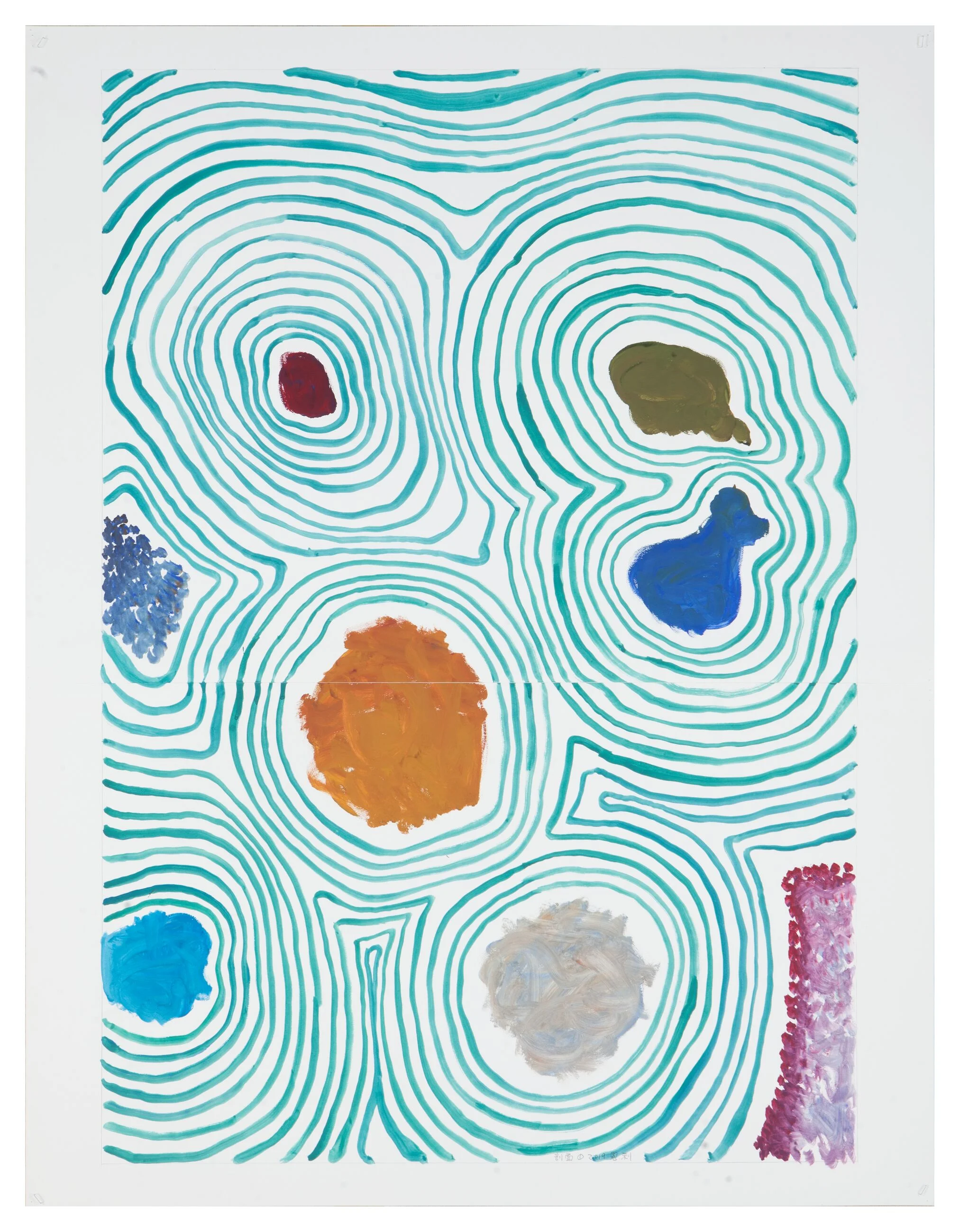

Zhang's artworks exude Chinese hints without being overt or simplistic. Some of the Destination works on display at Fortnum’s are on Chinese newspapers that the viewer can glimpse behind washes of white paint, while other works resemble the repeating pattern of tea fields in China's Yunnan province, and of course, Zhang's characteristic calligraphic strokes are rooted in the tradition of mark-making that dates back centuries if not millenia. These details of memory are masterfully hinted at and brought together throughout the series, particularly in the Profile works.

But conversely, it is the elements of Britishness that evoke a type of exoticism that could be considered less intellectual and more similar to the exoticism of yore. Could one consider this "Occidentalism" ?

The references jump off the pages: Fortnum’s characteristic colour of green is used to paint memories of Scottish landscapes and to fill in a drawing of a pond with phallic twigs protruding from its midst. The Tea Garden, which has been used for the limited edition printed Cashmere-blend scarf, is a crude use of the medium of watercolour, claimed by the artist to be an homage to the 18th-century British tradition of painting outdoors, while the artist blasphemously uses it as a rough, thick gouache, forgoing the transparency, malleability and delicacy associated with the use of watercolour by European Impressionists.

The artist and a representative from Hauser and Wirth acknowledged during a panel discussion at the exhibition's opening that Scottish whiskey had an influence on Zhang's work - how different is this indulgence to the 19th century opium-fuelled revelry that bohemian European travellers appropriated on journeys in the East [3]?

Twenty-two works (nineteen new works and three from previous exhibitions) are now hung in the shop on Piccadilly scattered between sunglasses and biscuits, hanging above a staircase or peeking through displays of fabric. A limited edition scarf and teapot have been produced as a result of the collaboration. But who are the audiences — and consumers —for this work? Who is Fortnum’s trying to target? The Queen and aristocrats whose emblems Zhang has simplified to mere marks of Fortnum's green or crude lines memorialising a highland kilt, or the tourists from China who visit the shop to buy tea and biscuits? The new visitors in Hong Kong, who will go to F&M’s first store outside the UK opening before the end of the year?

A hint might be provided by Ewan Venters, the CEO at F&M, when he says “It is a privilege to be working with Zhang Enli – one of the world’s greatest Chinese contemporary artists – to stimulate our visitors from around the world, in exciting visual and sensitive ways [...] at an incredibly important time for us as we prepare for our opening this Autumn in Hong Kong.”

Six further watercolour works will be produced for the Hong Kong store. It will be interesting to see what subjects the artist will choose to portray here.

The circles of complexity in the relationships on show ripple like Zhang's lines in the Profile series. If one is allowed to follow the train of thought. To think of the fact that the artist is inspired by the idyll of the English countryside, the nature he misses when he is back in China, the English mansions and roads and parks and museums that were funded by trade in tea [4], in opium [5], those industrious revolutions that caused the loss of nature in China in the first place.

What about this exoticism for a false idyll of the English countryside resonates with the artist? Is the artist finding himself or losing himself in the image of what Britishness is? Appropriately, a number of the works are titled “Destination” and look like abstracted maps of an imaginary place. These works almost act as a metaphor for the lost sense of place, that dangerous game of pretend, of romanticism that arises when working with the idealism of otherness.

Has the fact that this is an F&M commission influenced the artist in any way? Is it appropriate to have work influenced so greatly by a British brand? Or is it better because it has been mediated by a Swiss gallery? One could say that these are exactly the sorts of questions that contemporary art should be asking of us.

Don’t get me wrong in my questioning and critique. The commission is fascinating, thought-provoking and deep. It is inspiring to see how the brand of an artist elevates the discourse, and we have come a long way from the days when an anonymous artist painted a “Harem Scene” for a department store.

There is a lot there, a lot to think about. In these interesting times when Hong Kong residents are out protesting and when Britain’s foreign appeal needs all the help it can get, a bit of Occidental Exoticism might be the new movement we all need. Zhang Enli’s work is like a mirror, you may notice imperfections that are jarring, but there is a lot to reflect on, well after the fancy F&M doors close behind you.

Fortnum X Zhang Enli is on display until 18th October at Fortnum & Mason, London.

References

[1] For more about the links between Fortnum’s and the royal family, see this RadioTimes programme: https://www.radiotimes.com/tv-programme/e/hxm9z4/inside--inside-fortnum--mason-the-queens-grocer/

[2] See Figure 20, “Plate. Chinese (Dutch market) ca. 1740”; Figure 39, “Plate. Chinese (American market) ca. 1750-55”; “Plate, Chinese (American Market) ca. 1784-85. For the Society of the Cincinatti” Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3269266.pdf.bannered.pdf

[3] For more on 19th century opium use see Hayter, Alethea [1988]. Opium and the romantic imagination addiction and creativity in De Quincey, Coleridge, Baudelaire, and others. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire, England: Crucible, Distributed by Sterling Pub.

[4] “[...]in the nineteenth century [...t]here was high demand for Chinese team silk and porcelain on the British Market. However, Britain did not possess sufficient silver to trade with the Qing empire. Thus, a system of barter based on Indian opium was created to bridge this problem of payment.” http://blogs.bu.edu/guidedhistory/moderneurope/tao-he/

[5] “How Britain Went to War With China Over Opium” NYTimes 3 July 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/world/asia/opium-war-book-china-britain.html