The Feminine

In many ways, women dominate the preconceptions that surround Iran. The veil is a constant metaphor that Iranian women are hidden behind both literally and figuratively. Indeed, the whole country is oft personified as a coy lady waiting to be either defended by her own men or disrobed by others: from the Pahlavi-era rhetoric of the motherland to present-day world headlines riffing on some variation of ‘Lifting the Veil on Iran’. ‘Unveiling’ is an all too popular approach to acquainting oneself with the entire region of the Middle East, and by extension its art, something that reached its semantic peak with the 2009 Saatchi Gallery exhibition titled simply ‘Unveiled’.

Still cloaked in a sense of oriental mystery, any semblance of Iran’s ‘femininity’ in the public imagination is immediately tied to the veil. Nervous Westerners imagine spectres in full length, black chadors haunting the streets of Tehran, where in reality, save for the more conservative corners of society, women adapt the rules of compulsory hijab to suit fashion forward thinking. At the most extreme end of female agency, the ‘My Stealthy Freedom’ movement saw women removing their mandatory headscarves in a gesture of freedom in the face of government restrictions that have been in place since the 1979 Revolution. Resistance, as much as people perceive compliance, is part of the female condition in Iran.

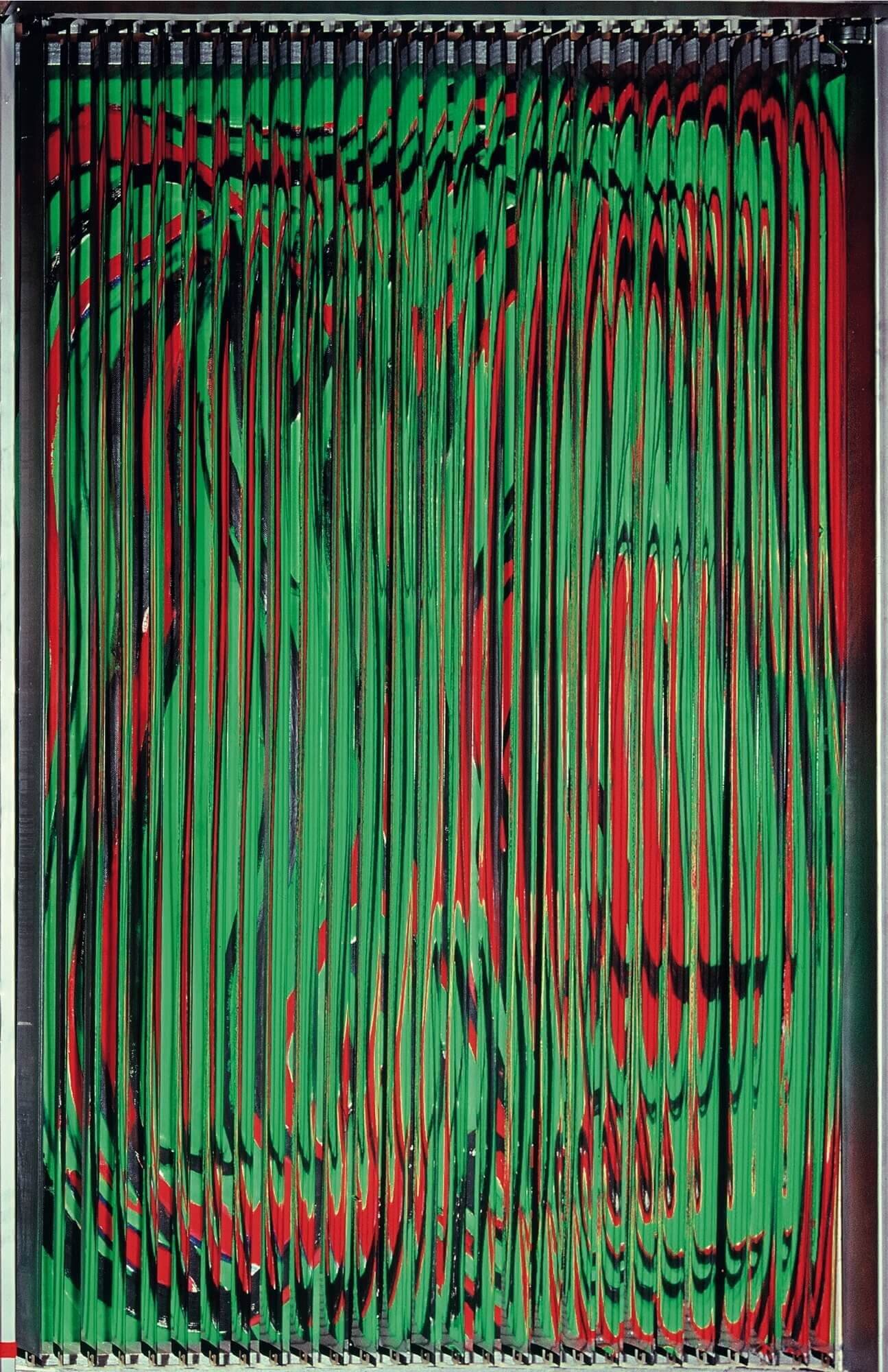

The tools that Iranian women artists use to dissect these issues surrounding femininity in their art are as serious as they are tongue-in-cheek. From the evocative simplicity of the pioneering female poets of the twentieth century, to a Lisa Frank-Brite kitsch, takes on what it is to be a woman in Iran are at once arch and searingly beautiful. Legendary artists, such as Behjat Sadr (1924 - 2009), worked crude oil into canvas for her own brand of intensely symbolic abstraction, taking her cues from her close friend and poet Farrokh Farrokhzad (1934 - 1967), whose verses were as thick with tumult and desire. The late Shirin Aliabadi (1973 - 2018) pioneered a subversive yet bubble-gum aesthetic of young Iranian womanhood in her Girls in Cars (2005) and Miss Hybrid (2008)series. From neon bright manicures to an altogether darker palette of viscous petrol, the modern Iranian woman crafts herself from both grit and glamour.

The surrealistic work of Hojat Khajavi (b.1982) plays on elements of ‘the divine feminine’: an emblem of spiritual energy at its most pure and a personal paean to flowing creativity. Women are often the sole subject of his work; their bodies are elevated, often literally, floating above invisible pedestals, or at the centre of spotlights, even as the centrifugal player within an orchestra. They are also equated with the grandeur of Persian antiquity; Khajavi buttresses his floating goddesses, dressed casually sans hijab in jeans and t-shirts, with the monumental processional archways of Persepolis. A girl, seated confidently on a rocking horse, appears to float through the Gate of All Nations with an unencumbered passage. As much as women are worshipped, however, they are also objectified. The two sides of the coin are turned by Khajavi. In Untitled ‘(2016), part of the Matador series, a young woman floats above a hamburger that is being held aloft by two genuflecting lion-like creatures, apparently modelled on the statuary of the ancient Persian empire. Above her tilted body reads the slogan ‘Bon Appetit’. In the collection of works under the title of Omen, women serenely strum the Persian tar (a traditional stringed instrument), whilst surrounded by men with arms outstretched, tumbling away from her in twirling acrobatics, never quite managing to touch.

Hojat Khajavi, Untitled, 2016

Parvin Jalali (b.1957) also plays on the goddess complex. Her work is vital and earthy, as if it were the recently uncovered evidence of a past civilisation. The series of pottery works, featuring a collection of terracotta coloured totems of female bodies, are a melange of the domestic and the divine. Similar themes run through her paintings: women and children emerge out of patchwork quilts, doors of houses open on to inquisitive babies, the trunks of trees twist into mythic maidens. In their riotous palette of turquoise and umber, they have a moralistic bombast. Jalali’s entire output is a testament to feminine power in all its guises: mothers, sisters, seductresses. Similarly, the work of Elmira Shokrpour (b. 1977) explores female companionship. Mixed media collage works are rich in pattern and texture. Her subjects are doll-like figures, often comforting each other in a sense of girlhood innocence and camaraderie. Each canvas is bestowed with a single word title that alludes to the predicament mulled over in its contents: Happiness, Libido, Forgiveness, Forgetfulness. In Jouissance (2018) and Duality (2018), both woman and girl face themselves as a Gemini double. There are elements of Pre-Raphaelite delicacy in the rendering of many of her subjects: ladies long of hair and even longer sleeve who wander through watery landscapes and arbours thick with branches. Her work operates on a level of tenderness and elegance but is shot through with a feeling of vulnerability. Jalali’s women are often followed by ominous black crows, their bare feet tread hurriedly over wet pavements, whilst a hand is tucked protectively between milky thighs.

Bita Vakili (b. 1973) brings the notion of the earth mother to a crescendo of crystal brightness. Each work in The Pulse of the Earth series (2017 – 2018) is centred around a cloud-like swirl of space shaped like a womb, encasing a small white foetus at its middle. Beautifully intricate, every piece appears as a cross section of a precious stone. Upon closer inspection, Vakili divides the space with sweeping lines of structural steel held in place with nuts and bolts, not out of place on a building site. At its most deliberately articulated, the Azad Tower of the nation’s capital, Tehran, juts out as if it were a prism at the centre of a line of light (Lullaby for Tehran, 2017). But why should the hardness of construction materials appear sturdier than the very geology of the earth? Vakili positions the planet as the ultimate creator, the ultimate mother, responsible for gestating both beauty and destruction at its core. Its veins are metallic, pumping both silver and gemstone brights through an umbilical cord of wispy, lace-like brushstrokes.

In an ode to the women of Persian past, Sadegh Tabrizi’s (b. 1939) Untitled makes use of the Qajar style figuration evocative of nineteenth century works on paper. A man carries a very satisfied looking woman on his back through drawn curtains, evoking the traditional separation between male and female space within Persian architecture (biruni and aruni respectively). The tea-stained surface of the work recalls the aged pages of classical Persian literature. Tabrizi has even gone as far as to overlay the couple with layers of fine script lifted from the ruled margins of a traditional tale. Rather than a damsel in distress waiting to be rescued, Tabrizi’s languid lady has more in common with the archetype of the female warrior, with a dagger tied with a baby blue sash at her waist, exemplified by characters such as Gordafarid in Ferdowsi’s poetic opus the Shahnameh. Gordafarid was a rosy cheeked beauty as feted in Persian poetry, but she also wasn’t averse to decking herself out in a knight’s armour either. In Tabrizi’s painting, the expression of serene delight worn by the woman is shared with the cat who walks beside them with a Cheshire grin. With her happy placation being apparent in her face, the sexual overtones of the composition are quite obvious. There is also little doubt as to her being in control.

Sadegh Tabrizi, Untitled

From the fearless femmes of Ferdowsi to the jean-wearing heroines of modern Tehran, contemporary Iranian artists show women in a kaleidoscopic vision of female power. Beauty and brawn go hand in hand, with the entire idea of womanhood finding its greatest resonance in the earth itself. Although there are borrowings from Iran’s deep history, there is the pervasive sense that the future is female.