Clarity in the Midst of Colour: the Paintings of J. Louis

‘A woman, for him, was not a body, but beauty incorporated in matter and acting through matter. That is why all his female figures, however solid, are not really of this world. They are symbols, unattainable dreams, like Sarah [Bernardt] when she came on to the stage, or died in the role of La Dame aux Camelias.’[i]

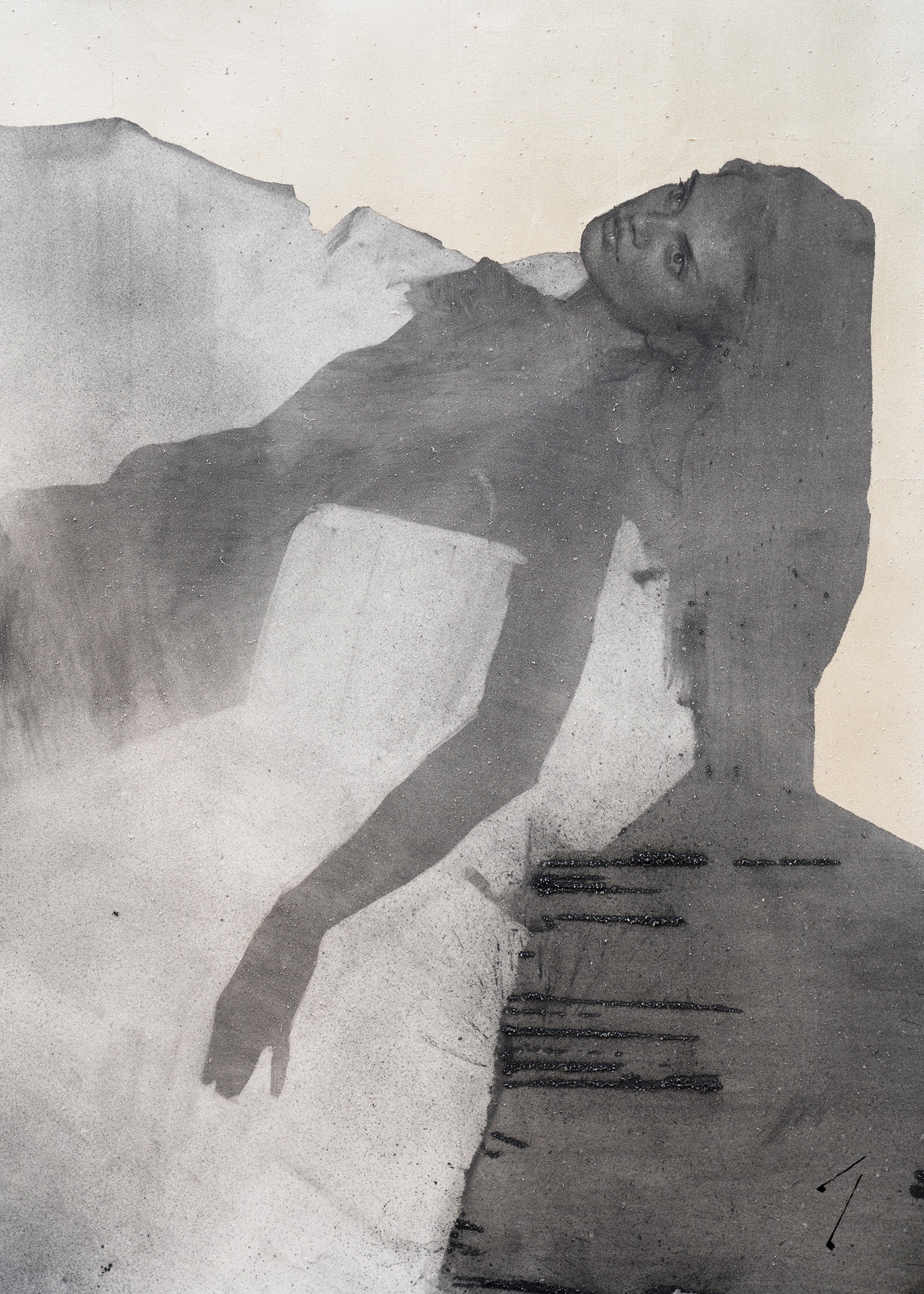

Women as subjects for admiration, representation and decoration, assume a prominent position in the art of J. Louis. Specific models seem to typify Louis’ style, lending inspiration to the artist. Their slight figures are elongated and sometimes placed horizontally within a tall, narrow format, which aesthetically enriches the composition and catches the beholder off guard. His women are often found reclining in languor, with flushed cheeks and gazes that are alternatively piercing and hazed by ecstasy.

He depicts women in a highly idealised state, undoubtedly as they would like themselves to appear. Indeed, notes of appreciation from his models’ reveal their thorough satisfaction with their portraits. ‘I paint women because of the impact so many women have had on me throughout my life,’ says Louis. ‘I was fortunate to grow up in an environment with strong women bursting with confidence and charisma. I was raised by two brilliant parents that encouraged me to push myself to succeed in any direction I felt best. When people see my work I want them to lose track of their thoughts because they have just made an instant connection with the person I have painted. I want people to see the beautiful qualities I see on the surface of my figures and the complexities beneath.’

The truth is that most of his women, by virtue of either their ‘otherworldly’ sensual expressions or near-absent surroundings, do not seem to be solidly planted in reality. It could be said that these paintings form an exercise in a sort of pictorial escapism, perhaps the sort which allows businessmen’s imagination to run wild for a brief solitary moment amidst appointments and meetings. But there, in part, lies the problem. How does Louis prevent his paintings from being merely an extension of furnishings intended to blend harmoniously with the decor of a rich man’s city office or apartment? How does a male artist draw or paint the female form with genuine appreciation for the woman in question and without objectifying women? Louis agrees that women should not be objectified as charming playthings; they should not be dressed up in lovely hues only to be arranged in alluring poses.

A precedent to Louis’ women was set by the Pre-Raphaelites. Their ideal required a specific type, generally tall and thin, endowed with sensuous lips, drooping eyelids and a profusion of hair. They share with Louis’ women at least one characteristic feature. Their faces contain a pensive or deliberately inscrutable expression. These women often seem to be wrapped in an otherworldly aura, detached from the mundane world. The corporeal and textural dynamics reveal to us the central dimension of ‘sex appeal’. Certainly, these women appear dark, melancholic and seductive. Yet others are bubbly, carefree and gay. What is the particular type of attractive female who graces Louis’ paintings? Is she a mercurial figure, or is she shown to us in different stages, and are all these paintings simply different manifestations of the same beauty-body?

Surprisingly perhaps, J. Louis was initially known for quite different subject matter. He started out producing minimalist but colourful paintings of animals; these are enjoyable though somewhat cartoonish creatures with open mouths and strange expressions transposed onto backgrounds of screaming pinks and yellows. Louis indulged the requests of his clients who were enamoured with the bright works.

‘When I first started painting I would paint whatever anyone wanted me to paint, which typically ended up being animals with an occasional portrait. I continued to paint animals for some time when I first started selling in galleries until I felt like I needed to follow a more powerful instinct to focus on figures. When I decided to paint figures my galleries were very worried that they wouldn’t sell anything. It was a complete gamble to make this transition, especially since I had decided that it was all or nothing. I decided to listen to myself and create figure work that I was fully invested in and proud of.’

In order to create first-rate figure work, he is very eager to learn from other artists; to learn how they design and orient motifs and forms. He tells me that he currently lives in Chicago, ‘where there are very few professional artists who have a taste that is similar to mine, so it has been rather isolating.’ He is currently moving to New York City, in part to be a little geographically closer to his peers. It should be said that he is equally keen on sharing his own tricks with budding artists through workshops and seminars and expresses his desire to fill ‘halls of museums, homes of loving collectors, and facades of buildings with my artistic messages.’

But what exactly are Louis’ artistic messages, and where does the man behind the message come from? J. Louis was born Joshua Brown in Karlsruhe, Germany, to a family which was always on the move due to his father’s military occupation. His mother, who has Scandinavian roots, was an ‘energetic opera singer, quick to support us in our interests and excited to leave our minds full of uninhibited confidence’.

Louis has lived in the United States for most of his life. As goalkeeper in the Olympic development pool for the national soccer team, Louis won a full soccer scholarship to attend SCAD (Savannah College of Art and Design). Here he studied Industrial Design and collaborated with designers from across the world. Somehow, between sweaty football fields and lecture halls, this freshman did not only find time to produce a series of paintings, but also to court a woman in the dorm across: Lillian Mueller, whom he married four years later.

Louis readily speaks of his adoration for his wife Lilly; her Swiss heritage, her natural grace, and the strength of her character. He notes on how he is constantly struck by sparks of connection and affection, and how these electrifying experiences egg him on. His wife is a visual designer with a knack for photography, who is, in Louis’ words, ‘a person full of empathy and full of the courage to question everything’.

His wife is not the only artist who serves as a source of inspiration for Louis. The French Impressionists (especially Monet and Degas), American Expressionists (Rothko) the Vienna Secessionists (Klimt and Schiele), Anders Zorn, Sargent and Antonio Mancini are influences too. But Egon Schiele is perhaps the most recognisable source of inspiration: the way Louis poses the twisted bodies and detailed faces of his models, putting them in a completely bare and abstract world, is slightly reminiscent of the Viennese artist. ‘The way Egon Schiele painted hands, it’s simply incredible how he moves those around; how he organised space.’

Louis also elaborates on his love for Klimt. Gustav Klimt, the first president of the Vienna Secession, crafted a kind of woman typical of Art Nouveau. In his portraits of society women, he strikes a balance between faithful representation of the sitter’s features and the elaborate piling-up of ornament encompassing clothing (in addition to which the background often is a dense arrangement of mosaic-like forms). We find a similarly exciting contrast between facial clarity and surrounding abstractions in Louis’ work. Louis, however, does not necessarily follow in Klimt’s footsteps blindly. Klimt obliterates the three-dimensionality, and thus the living reality, of his women by weighing them down under an excess of two-dimensional geometric ornament and detail. The focus Louis places on his women's faces, however, lends his paintings a frieze-like effect; parts of the female body seem to stick out of the canvas. The hands, too, are sometimes carefully rendered, then smothered by a massing of colour and shape. The effect tends to place the human body in high relief juxtaposed as it is by multi-faceted, multi-coloured areas of decoration. In this respect, Louis’ and Klimt’s works differ radically.

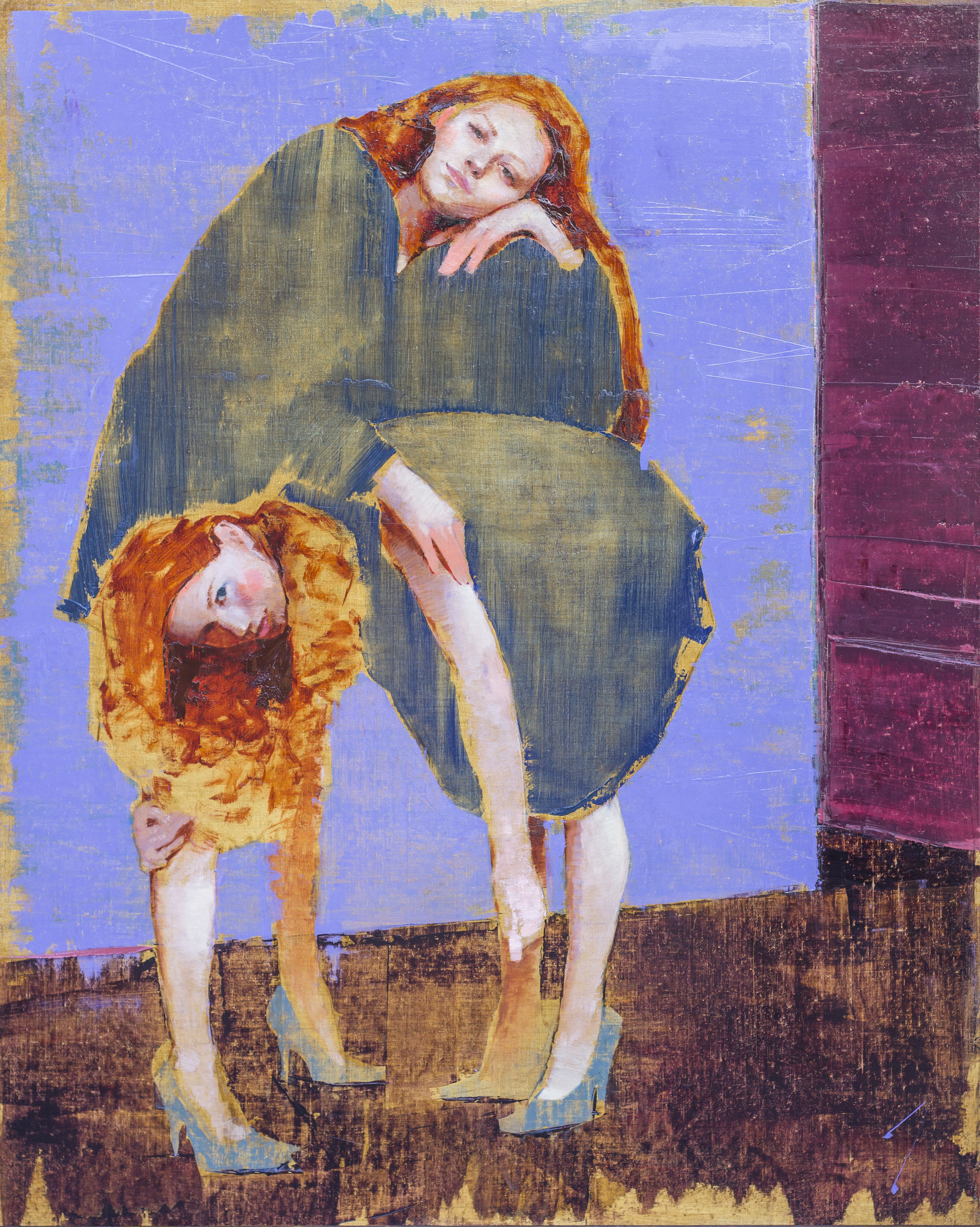

Exaggerations of women’s hair was repeatedly used as a dominating motif by Art Nouveau artists, almost to the point of obsession, thereby extending the erotic qualities already associated with women. In this Louis’ women are not unlike. His women do not transcend their sex by unconventionality; they do not appear in male attire nor do they affect male attitudes. They embody the standards of beauty which our society demands from women. However, Louis’ paintings are not decadent or baroque; the absence or ornament lends makes them pleasant to look at. In his works women are definitely not zealously patronised as fragile, helpless objects; they appear fierce and emerge bursting from vibrant fields of colour.

How does he go about making his works? He designs a mood board of images and colour schemes, incorporating photographs he has taken of models, and tries to fashion some sort of story out of this. He does manipulate his reference photos in order to give himself more freedom in the creative process. His early set of figure paintings is dominated by bright greens and yellows, whereas the pinks and reds of lush human flesh dominate the more recent ones. A painting which I find most touching, and which has an interesting viewpoint, is Chicago (2018). On closer inspection it turns out to be a portrait of his wife. Light is graciously reflected in one eye, whilst the other part of her face is covered in some shadow. Praiseworthy are the fragility of Leaning (2016), the darker colours used in Hands Above (2018) (apparently Louis came home one day determined to paint a portrait of his “beautiful wife” using the “ugliest colour in the world”), the funkiness of Interweave (2016) and Interweave II (2017). I especially love a somewhat cubistic and brown portrait he made of his wife in 2016.

In Interweave (2016) we're presented with a pair of swarthy girls who appear to be twins: one can easily appreciate the stark contrast between the rough surfaces that represent their clothes and the silkier texture of their skin. The restrained and dulled hue of the colours here also works beautifully.

For a young artist on the outset of his career, J Louis has already experimented and painted an awful lot, and his art has met with deserved praise. Admittedly, there is challenge in making all these perfectly charming women seem less similar. In our culture where women continue to be featured as cunning advertising attractions and as objects of designers’ whims, it is important to find and emphasise their idiosyncrasies and flaws—or at least what society perceives to be women’s flaws—rather than exaggerate their perfection, in order to uncover the true story behind their beauty. These complexities are already shimmering beneath the surface of the faces of Louis’ women, and once he draws them out completely, he will be a very accomplished artist indeed. Not just as a painter, but as a sculptor too. ‘In addition to painting, I am working on a body of sculptures that I hope to unveil in the next few years.’ He has set himself a difficult task, but as a man who loves strength, courage and independence in women, he must succeed.

Edmond Duranty, in 1885, told us that it takes immense genius to represent, simply and sincerely, what we see in front of us. ‘I see my wife’s face,’ says Louis. ‘It’s the first thing I see in the morning and the last thing I see at night.’ Her face, and the woman behind the face, is like a rock in a foaming sea of change for Louis; it is the one point of focus and clarity amidst the mists and uncertainties of an artist’s life.

On a final note, Louis remarks that he was strangely energised by the hotness and humidity during a trip to Bali, and that he noticed more ideas come to him in airplanes and fast-trains, in arrivals and departures. It is interesting that movement should stimulate him so; it seems as though the energy that drove his athletic pursuits also drives his artistic endeavours. He speaks of the physical energy of art (and there is an undeniable dynamism in his own brushstrokes); something, he claims, that cannot be conveyed through a digital copy. He urges museum-goers to linger longer by artworks than they normally would, because artworks, when seen in person, begin to whisper truths only to those who are prepared to wait and listen.

[i] Jiří Mucha describing his father, Alphonse Mucha, qtd in Victoria Duckkett’s Seeing Sarah Bernhardt: Performance and Silent Film, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2015), p.34

J. Louis has work at Arcadia Contemporary in Culver City, CA and Shain Gallery in Charlotte, NC.