At the Violet Hour: Reanimating T.S. Eliot's 'Inviolable Voices'

On Margate Sands. / I can connect / Nothing with nothing. / The broken fingernails of dirty hands. / My people humble people who expect / Nothing.

T. S. Eliot, ‘The Fire Sermon’.

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives / Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea, / The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights / Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

T. S. Eliot, ‘The Fire Sermon'.

October 1921. The British poet T. S. Eliot travelled down to Margate to recuperate after suffering a nervous breakdown, buckling under the weight of his failing marriage and the pressure of completing The Waste Land (1922). He’s thought to have drafted ‘The Fire Sermon’, the third section of this work – which would come to represent one of the defining poetic compositions of the Modernist era – in a Victorian seaside shelter, an open timber structure that still stands today, overlooking Nayland Rock. Nearly a century later, Chiara Williams and Shaun Stamp's exhibition has opened in the Nayland Rock Hotel. At the Violet Hour brings together nationally and internationally known artists who are inspired by the poem and the ‘inviolable voices’ that invest its text, the myriad faces, the stories, and the ‘heap of broken images’ that emerge from Eliot’s ‘unreal city’.

The Nayland Rock Hotel provides a stunning backdrop to the exhibition’s installations. Its heritage is undeniable. Built in 1886, it was once one the grandest holiday destinations on the south coast, the toast of tourists and stars alike. Regency wallpaper decorated its corridors, stairways, and bedrooms. Wrought-iron railings lined its balconies. Guests strolled leisurely through the landscaped gardens, before settling in ornate dining rooms and lounges. Here, they enjoyed unrivalled views of the whole of Margate, the coast, and the Channel. In the present, however, this grandeur has faded, the hotel that Eliot would have known from that brief sojourn almost unrecognisable. The sea and the coastline remain but the gardens have gone, sold off to developers years ago. Two of the hotel’s upper floors were destroyed by a fire in the 80s, never to be rebuilt. The wallpaper is now discoloured, peeling to reveal dirty chipboard; the walls themselves are damp and mildewed; the window and mirror panes cracked and stained, the frames browned, some boarded up. In the last decade, it was used to house newly arrived refugees. Recently, it has been sold to new owners, presumably to be refurbished completely thus effectively erasing the last of the hotel’s heritage and history.

Interior of the Nayland Rock Hotel

There’s an unsettling disquiet to this place. Every room of the hotel teems with forgotten voices, a whispering that accompanies the smack of the surf, the sea and rain-flecked wind outside. This is a space that appears suspended in time, and a setting that, in its decayed and crumbling state, inevitably recalls the long-forgotten ‘memory and desire’ that begins The Waste Land, emerging from the dead world of modern society. Thus, At the Violet Hour finds its perfect home here, a liminal space where the voices of Eliot’s poem and the past can find new articulation and definition in the paintings, sculpture, and installations that both inhabit and reanimate the hotel’s numbered rooms across its four floors. The pieces focus on a few select themes that dominate ‘The Fire Sermon’, especially: the power of myth; the nature of gender; the construction of the self; sex, and sexual violence, all linked to some extent through the figure of the blind yet all-seeing prophet Tiresias. Susie Hamilton emphasises this figure, seeking to convey the chaotic and fragmentary nature of the poem and Tiresias’s own omniscience in her work on paper in ‘These fragments’: drawings and paintings from ‘The Waste Land’. Broad brush strokes, swathes of colour, chiaroscuro and indistinct, often grotesque figures are all features of these pieces, as she depicts characters and scenes from the whole of The Waste Land, out of time and sequence, an attempt to reflect, perhaps, the prophet’s own disordered perspective on the world.

Many of the exhibition’s installations are dependent on the participation of their audiences. Jessica Jordan-Wrench’s phonebooth, for example, places the viewer in an intimate call with one of The Waste Land’s major female characters: The Typist. The viewer must enter the phonebooth alone, pick up the ringing handset, before listening to the Typist’s looped monologue, words filled with all the sadness, infatuation, and despair of Eliot’s text, but pieced together from clippings from films over the past twenty years. She speaks to us in words and a voice that are not her own. Similarly, Lindsay Segall’s Fight in Room 421 is a film that details an emotional, anger-filled encounter between two lovers in the middle of an affair, an encounter highly reminiscent of the Typist’s.. The scene is violent; the man attempts to force himself upon the woman. Wine glasses are smashed, thrown at the walls, and the glass fragments remain in the room for the viewer to see, lining the cupboards, bed, and floors identical to those on the screen. The effect is disturbing. It’s as if the onlooker is forced to rediscover their own repressed memory; like Tiresias, we’re made to witness and thus relive the encounter ourselves, as it happens around us in real time.

The sexual abuse of women is also the subject of Victoria Lucas’s Conversing with Tiresias. Here, the artist herself takes on the role of prophetic clairvoyant, reading out a script that hints at the events that have taken place in Room 418. The piece intersperses quotations from Eliot’s ‘Fire Sermon’, in which the blind prophet watches the rape of the Typist but does nothing, with historic accounts of sexual assault made against the film producer Harvey Weinstein. The similarities between the two are striking. At times, it is hard to distinguish them. There’s even a plant pot in the corner, whose appearance needs no explanation in light of the stories from Weinstein’s accusers. In the exhibition’s opening space, Katie Louise Surridge reinterprets the metamorphosis of Philomel, who, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, is raped and silenced by having her tongue cut out, before finally fleeing to safety by transforming into a bird. Here, Philomel’s wings are steel-forged, hardened, made from hundreds of hand-crafted acanthus leaf decorations and then welded together. Surridge gives Philomel a far greater agency than Ovid or Eliot did; she becomes the means of her own escape, her wings her own invention, much like that of Daedalus.

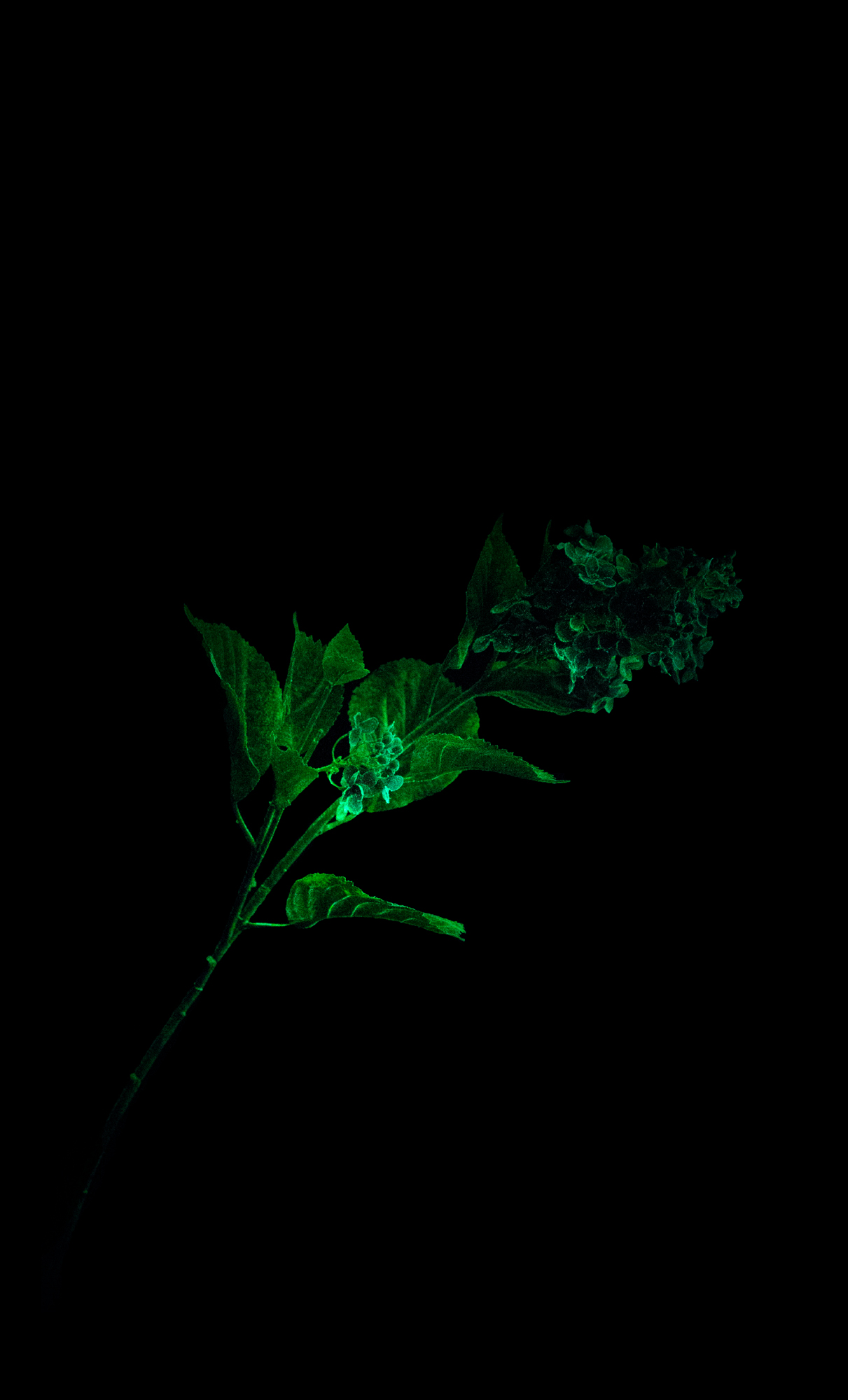

Shaun Stamp takes the central motif of the ‘lilacs’ rising out of The Waste Land as the inspiration for his work. In one bathroom, a diptych of glow-in-the-dark lilac flowers sit behind a dirty shower curtain, while up above, on a railing, a nightingale surprises the viewer, gazing at the flowers on the wall, highlighting the contrast between the natural and its unnatural surroundings. Meanwhile, Emma Critchley’s Do You Know Nothing? Do You See Nothing? Do You Remember, Nothing? seeks to reflect the disordered perception of time in the poem, conflating future and present, transforming her room into a space that floods at high tide, the residue of this sea water visibly staining its walls. The room, and by extension the hotel itself, becomes a prophetic vision of the effect of climate change, and the effect of rising sea levels.

The exhibition presents so many interesting new perspectives and interpretations on Eliot’s poem and modern life across its four floors: Paul Knight’s meditation on Nietzsche’s ‘Eternal Reoccurrence’ and the connection of melancholia to remembered experience in Room 316; Chiara Williams’ Hush, which interrogates the cinematic framing of women’s bodies, and Emma Critchley’s We Do Not Know What We Cannot Name, which explores how language shapes the way we perceive and connect with the world are all particular highlights. There are even two rooms on different floors devoted to the film-maker Derek Jarman and his debt to Eliot’s poem, with items including Jarman’s own copy of the The Waste Land loaned from the Derek Jarman estate. At the Violet Hour’s success lies in its use of such a unique space, the decaying, crumbling Nayland Rock Hotel. It creates an environment in which the viewer truly experiences something of the uncanny, ‘inviolable voices’ of Eliot’s Waste Land. Where they emerge, half-whispered, articulating themselves like so many echoes through desolate and half-empty rooms.

At the Violet Hour is on show from 3 February - 11 March, 2018, at the Nayland Rock Hotel, Margate. Curators: Chiara Williams and Shaun Stamp.